NAIROBI, Kenya - Millions of people in drought-stricken East Africa face hunger and poverty after seasonal rains failed again, withering crops, killing livestock and drying up ponds and streams, an aid group said Thursday.

Oxfam said some areas had received less than 5% of normal rainfall for November. In war-ravaged Somalia, it is the sixth failed rainy season and the worst drought for 20 years. The failed state is already being torn apart by a brutal civil war that means nearly half its population relies on aid.

Diplomats said the suffering underscores the need for an agreement to combat climate change. African delegates at the Copenhagen talks on climate change have repeatedly accused rich industrialized countries of polluting the atmosphere with greenhouse gases and then leaving underdeveloped countries to deal with the resulting drought and starvation on their own.

"We face a disastrous situation in the Horn of Africa that demonstrates the terrible potential of climate change. This crisis, which is happening now, underlines why it is so important to reach an agreement in Copenhagen," said Karel De Gucht, the European Union's development commissioner.

The European Commission said it would immediately release an extra $75 million to fund emergency relief for drought-stricken areas in the Horn of Africa. It estimates 16 million people will need aid in the coming months.

Oxfam said in its report that the failure of the November "short" rains in many pockets of East Africa after several dry seasons will intensify hunger and disease. Heavily used and polluted water sources have not been replenished. Millions of people are at risk in Kenya, Ethiopia, Somalia, Uganda and Tanzania, Oxfam said.

The semiarid and arid areas depend on the October-November rainfall, called the short rains, for most of their water needs for the year. A failure of the rains means those areas will have poor or no harvests for the coming year.

"More must be done to invest in helping these communities cope with the dry years — through long-term rural development and investing in national agriculture. But in the short-term lives are at stake and emergency aid is needed now," said Jeremy Loveless, Oxfam's deputy humanitarian director.

A September report by the International Food Policy Research Institute predicted that the worldwide effects of climate change will lead to twenty-five million additional children becoming malnourished by 2050. Aid agencies have long said that droughts are becoming more frequent in Africa, where many living in arid areas are particularly vulnerable to changes in the weather.

Oxfam said cattle prices have tumbled from $200 to $4 in some areas as families try to sell dying animals to buy a few handfuls of corn. Over 1.5 million animals have died in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda, with an estimated net worth to the region of nearly $360 million, Oxfam said.

For many nomadic families living without access to banking facilities, cattle represent their only wealth. The animals' deaths begin a spiral into poverty and dependency that can trap a family for generations. Families have even shared relief grain with their animals, trying to keep at least a few alive to restock in the future.

"The population can no longer cope with such extreme and protracted hardship which often comes on top of conflict situations," De Gucht said.

In addition to the war in Somalia, rebel groups are battling the central government in Ethiopia, which has restricted access to aid agencies. In northern Kenya and parts of Uganda, heavily armed ethnic militias conduct cattle raids and fight over precious grazing ground and water.

Copyright 2009 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/34462971/ns/weather/

Wednesday, December 30, 2009

Tuesday, December 15, 2009

PNAS: Special Issue on Tipping Elements

Excerpt from a summary:

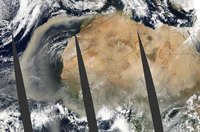

Tipping element Bodélé Depression: The immense dust storm was imaged in a series of overpasses by the NASA’s Aqua satellite. Image courtesy Jacques Descloitres, MODIS Rapid Response Team, NASA-Goddard Space Flight Center

Tipping element Bodélé Depression: The immense dust storm was imaged in a series of overpasses by the NASA’s Aqua satellite. Image courtesy Jacques Descloitres, MODIS Rapid Response Team, NASA-Goddard Space Flight Center

A research team led by Richard Washington from the University of Oxford qualifies the biggest dust source on our planet, the Bodélé Depression in Chad, as a potential tipping element. This area in the southern Sahara releases huge plumes, which carry about 700,000 tons of dust towards the Atlantic and the Amazon basin. The authors explain that the so-deployed mineral aerosols play a vital role in transcontinental climatic and biophysical feedbacks. If regional wind patterns or surface erosivities changed due to anthropogenic interference, the dust export from the Bodélé Depression could be substantially modified at time scales as small as one season.

Wednesday, December 2, 2009

John Vidal, The Guardian: Kenya's droughts increase in frequency

'Climate change is here, it is a reality'

As one devastating drought follows another, the future is bleak for millions in east Africa. John Vidal reports from Moyale, Kenya

by John Vidal, The Guardian, September 3, 2009

One of the main water sources outside Moyale in Kenya runs dry. Photograph: Sarah Elliott/EPA

We met Isaac and Abdi, Alima and Muslima last week in the bone-dry, stony land close to the Ethiopia-Kenya border. They were with five nomad families who have watched all their animals die of star vation this year in a deep drought, and who have now decided their days of herding cattle are over.

After three years of disastrous rains, the families from the Borana tribe, who by custom travel thousands of miles a year in search of water and pasture, have unanimously decided to settle down. Back in April, they packed up their pots, pans and meagre belongings, deserted their mud and thatch homes at Bute and set off on their last trek, to Yaeblo, a village of near-destitute charcoal makers that has sprung up on the side of a dirt road near Moyale. Now they live in temporary "benders" – shelters made from branches covered with plastic sheeting. They look like survivors from an earthquake or a flood, but in fact these are some of the world's first climate-change refugees.

For all their deep pride in owning and tending animals in a harsh land, these deeply conservative people expressed no regrets about giving up centuries of traditional life when we spoke to them. Indeed, they seemed relieved: "This will be a much better life," said Isaac, a tribal leader in his 40s. "We will make charcoal and sell firewood. Our children will go to the army or become traders. We do not expect to ever go back to animals."

They are not alone. Droughts have affected millions in a vast area stretching across Kenya, Somalia, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Sudan, Chad, and into Burkina Faso and Mali, and tens of thousands of nomadic herders have had to give up their animals. "[This recent drought] was the worst thing that had ever happened to us," said Alima, 24. "The whole land is drying up. We had nothing, not even drinking water. All our cattle died and we became hopeless. It had never happened before. So we have decided to live in one place, to change our lives and to educate our children."

Parched

Kenya, a land more than twice the size of Britain, is everywhere parched. Whole towns such as Moyale with more than 10,000 people are now desperate for water. The huge public reservoir in this regional centre has been empty for months and, according to Molu Duka Sora, local director of the government's Arid Lands programme, all the major boreholes in the vast semi-desert area are failing one by one. Earlier this year, more than 50 people died of cholera in Moyale. It is widely believed that it came from animals and humans sharing ever scarcer water.

Food prices have doubled across Kenya. A 20-litre jerrycan of poor quality water has quadrupled in price. Big game is dying in large numbers in national parks, and electricity has had to be rationed, affecting petrol and food supplies. For the first time in generations there are cows on the streets of Nairobi as nomads like Isaac come to the suburbs with their herds to feed on the verges of roads. Violence has increased around the country as people go hungry.

"The scarcity of water is becoming a nightmare. Rivers are drying up, and the way temperatures are changing we are likely to get into more problems," said Professor Richard Odingo, the Kenyan vice-chair of the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

"We passed emergency levels months ago," said Yves Horent, a European commission humanitarian officer in Nairobi. "Some families have had no crops in nearly seven years. People are trying to adapt but the nomads know they are in trouble."

Many people, in Kenya and elsewhere, cannot understand the scale and speed of what is happening. The east African country is on the equator, and has always experienced severe droughts and scorching temperatures. Nearly 80% of the land is officially classed as arid, and people have adapted over centuries to living with little water.

There are those who think this drought will finish in October with the coming of the long rains and everything will go back to normal.

Well, it may not. What has happened this year, says Leina Mpoke, a Maasai vet who now works as a climate change adviser with Ireland-based charity Concern Worldwide, is the latest of many interwoven ecological disasters which have resulted from deforestation, over-grazing, the extraction of far too much water, and massive population growth.

"In the past we used to have regular 10-year climatic cycles which were always followed by a major drought. In the 1970s we started having droughts every seven years; in the 1980s they came about every five years and in the 1990s we were getting droughts and dry spells almost every two or three years. Since 2000 we have had three major droughts and several dry spells. Now they are coming almost every year, right across the country," said Mpoke.

He reeled off the signs of climate change he and others have observed, all of which are confirmed by the Kenyan meteorological office and local governments. "The frequency of heatwaves is increasing. Temperatures are generally more extreme, water is evaporating faster, and the wells are drying. Larger areas are being affected by droughts, and flooding is now more serious.

"We are seeing that the seasons have changed. The cold months used to be only in June and July but now they start earlier and last longer. We have more unpredictable, extreme weather. It is hotter than it used to be and it stays hotter for longer. The rain has become more sporadic. It comes at different times of the year now and farmers cannot tell when to plant. There are more epidemics for people and animals."

'We have to change'

Mpoke said he did not understand how people in rich countries failed to understand the scale or urgency of the problem emerging in places such as Kenya. "Climate change is here. It's a reality. It's not in the imagination or a vision of the future. [And] climate change adds to the existing problems. It makes everything more complex. It's here now and we have to change."

The current drought is big, but the nomads and western charities helping people adapt say the problem is not the extreme lack of water so much as the fact that the land, the people and the animals have no time to recover from one drought to the next. "People now see that these droughts are coming more and more frequently. They know that they cannot restock. Breeding animals takes time. It take several years to recover. One major drought every 10 years is not a problem. But one good rainy season is not enough," said Horent.

Nor are traditional ways of predicting and adapting to drought much use. In the past, said Ibrahim Adan, director of Moyale-based development group Cifa, nomads would look for signs of coming drought or rain in the stars, in the entrails of slaughtered animals or in minute changes in vegetation. "When drought came, elders would be sent miles away to negotiate grazing rights in places not so seriously hit, and cattle would be sent to relatives in distant communities. People would reduce the size of their herds, selling some and slaughtering the best to preserve the best meat to see them through the hard times. None of that is working now."

Francis Murambi, a development worker in Moyale, said: "The land has changed a lot. Only 60 years ago, the land around Moyale was savannah with plenty of grass, big trees and elephants, lions and rhino." Today the grasses have all but gone, taken over by brush. Because there are fewer pastures, they are more heavily used. It's a vicious circle. In the past, a nomadic family could live on a few cows which would provide more than enough milk and food. Now the pasture is so poor that those who still herd cattle need more animals to survive. But having more cattle further degrades the soil. The environment can support fewer and fewer people, but the population has increased.

"[Before] we did not need money. The pasture was good, the milk was good, and you could produce butter. Now it is poor, it is not possible," said Gurache Kate, a chief in Ossang Odana village near the Ethiopian border. "Yesterday I had a phone call from the man we sent our cattle away with. He is 250 miles away and he said they were all dying."

These shifts driven by climate change are bringing profound changes. Ibrahim Adan said: "The cow has always been your bank. Being a Borana means you must keep livestock. It's part of your identity and destiny. It gives you status. Traditionally livestock was central to life. The old people saw cattle as the centre of their culture. Pride, love and attachment to cattle was all celebrated in song. My father would never sell cattle. They were an extension of himself."

Now, for people like Isaac and Abdi, Alima and Muslima, all that is gone, and with it independence and self-sufficiency. "The money economy is creeping in, as is education and the settled life," said Adan. "Young people see the cow now as more of an economic necessity rather than the core of their culture."

The great unspoken fear among scientists and governments is that the present cycle of droughts continues and worsens, making the land uninhabitable. "This isn't something that will just affect Kenya. What is certain is that if climate change sets in and drought remains a frequent visitor, there will be far fewer people on the land in 20 years," said Adan. "The nomad will not go. But his life will be very different."

Link: http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2009/sep/03/climate-change-kenya-10-10

Saturday, November 28, 2009

by Meles Zenawi, The Guardian: Climate change will hit Africa hardest

Climate change will hit Africa hardest

Having bailed out bankers, can developed counties really oppose funds to help developing nations fight global warming?

by Meles Zenawi, guardian.co.uk, 28 November 2009

Climate change will hit Africa – a continent that has contributed virtually nothing to bring it about – first and hardest.

Aside from Antarctica, Africa is the only continent that has not industrialised. Indeed, since the 1980s the industrialisation that had taken place in Africa has by and large been reversed. Africa has thus contributed nothing to the historical accumulation of greenhouse gases through carbon-based industrialisation. Moreover, its current contribution is also negligible, practically all of it coming from deforestation and degradation of forests and farmland.

Yet climate change will hit Africa hardest, because it will cripple the continent's vulnerable agricultural sector, on which 70% of the population depends. All estimates of the possible impact of global warming suggest that a large part of the continent will become drier, and that the continent as a whole will experience greater climatic variability.

We know what the impact of periodic droughts have been on the lives of tens of millions of Africans. We can therefore imagine what the impact of a drier climate on agriculture is likely to be. Conditions in this vital economic sector will become even more precarious than they currently are.

Africa will not only be hit hardest, but it will be hit first. Indeed, the long dreaded impact of climate change is already upon us. The current drought covering much of east Africa – far more severe than past droughts – has been directly associated with climate change.

The upcoming climate negotiations in Copenhagen ought to address the specific problems of Africa and similarly vulnerable poor parts of the world. This requires, first and most importantly, reducing global warming to the apparently inevitable increase of 2C, beyond which lies an environmental catastrophe that could be unmanageable for poor and vulnerable countries. Second, adequate resources should be made available to poor and vulnerable regions and countries to enable them to adapt to climate change.

Climate change, which was largely brought about by the activities of developed countries, has made it difficult for poor and vulnerable countries to fight poverty. It has created a more hostile environment for development. No amount of money will undo the damage done. But adequate investment in mitigating the damage could partly resolve the problem.

Developed countries are thus morally obliged to pay partial compensation to poor and vulnerable countries and regions to cover part of the cost of the investments needed to adapt to climate change.

Various estimates have been made of the scale of investment required by those countries. One conservative estimate – which has a reasonable chance of being accepted precisely because it is conservative – calls for $50bn per year as of 2015, increasing to $100bn by 2020 and beyond. A transitional financing arrangement would be put in place for the period 2010-2015.

Some argue that developed countries cannot come up with such sums, particularly given their current economic challenges. But no one has so far argued that the cost of damage caused to the development prospects of poor countries and regions is less than the amount of compensation being offered to cover adjustment costs. The reason is obvious: the damage caused is many times higher than the compensation being requested.

Nonetheless, it is argued, whatever the real cost of the damage, developed countries currently cannot afford to provide that kind of money. But we all know that these countries and their national banks were able to spend trillions of dollars in a few months to bail out their bankers, who earned super-profits when the going was good. When the good times ended, taxpayers and governments were prepared to rescue them and to ensure that they continued to receive their extraordinary bonuses.

If the developed world is able to pay trillions of dollars to clean up its bankers' mess, how is it possible that it cannot afford to pay billions of dollars to clean up a mess that it created, and that is threatening the survival of whole continents?

Clearly this is not about the availability of resources. It is about the inappropriate priorities in how resources are allocated. It is about moral values that make it appropriate to rescue bankers, who expect everyone but themselves to pay for the mess they created, and inappropriate to compensate the world's poorest people, whose survival is threatened precisely because of the mess created by developed countries.

I cannot believe that people in developed counties, when informed about the issues, would support rescuing bankers and oppose partial compensation for poor countries and regions. I cannot believe that they will let such an injustice occur. If they are not expressing their outrage over the injustice of it all, it can only be because they are inadequately informed.

Link: http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/cif-green/2009/nov/28/africa-climate-change

Wednesday, November 25, 2009

From past to future agricultural expertise in Africa: Jola women of Senegal expand market-gardening

This seems to be one of those papers that was written only to establish a well-known fact.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Published online before print November 24, 2009, doi:10.1073/pnas.0910773106

From past to future agricultural expertise in Africa: Jola women of Senegal expand market-gardening

Olga F. Linares*

Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Diplomatic Post Office AA 34002-9998

Contributed by Olga F. Linares, October 7, 2009 (sent for review August 2, 2009)

Abstract

*E-mail: linareso@si.edu

Link to abstract: http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2009/11/23/0910773106.abstract

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Published online before print November 24, 2009, doi:10.1073/pnas.0910773106

From past to future agricultural expertise in Africa: Jola women of Senegal expand market-gardening

Olga F. Linares*

Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Diplomatic Post Office AA 34002-9998

Contributed by Olga F. Linares, October 7, 2009 (sent for review August 2, 2009)

Abstract

Jola women farmers in the Casamance region of southern Senegal use their “traditional” knowledge and farming skills to shift crop repertoires and techniques so as to embark on market-gardening, thus innovating in response to new needs and perceived opportunities. The argument is relevant to present-day concerns about regional food systems and the role of women in securing an income and providing extra food for the family.

*E-mail: linareso@si.edu

Link to abstract: http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2009/11/23/0910773106.abstract

Tuesday, November 24, 2009

Climate (temperature increases) a major cause of conflict in Africa

Climate 'is a major cause' of conflict in Africa | ||||

Climate has been cited as a factor behind civil conflict in Darfur Climate has been a major driver of armed conflict in Africa, research shows -- and future warming is likely to increase the number of deaths from war. US researchers found that across the continent, conflict was about 50% more likely in unusually warm years. Writing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), they suggest strife arises when the food supply is scarce in warm conditions. Climatic factors have been cited as a reason for several recent conflicts. One is the fighting in Darfur in Sudan that according to UN figures has killed 200,000 people and forced two million more from their homes.

Previous research has shown an association between lack of rain and conflict, but this is thought to be the first clear evidence of a temperature link. The researchers used databases of temperatures across sub-Saharan Africa for the period between 1981 and 2002, and looked for correlations between above average warmth and civil conflict in the same country that left at least 1,000 people dead. Warm years increased the likelihood of conflict by about 50% -- and food seems to be the reason why. "Studies show that crop yields in the region are really sensitive to small shifts in temperature, even of half a degree (Celsius) or so," research leader Marshall Burke, from the University of California at Berkeley, told BBC News. "If the sub-Saharan climate continues to warm and little is done to help its countries better adapt to high temperatures, the human costs are likely to be staggering." Conflicting outcomes If temperatures rise across the continent as computer models project, future conflicts are likely to become more common, researchers suggest.

Their study shows an increase of about 50% over the next 20 years. When projections of social trends such as population increase and economic development were included in their model of a future Africa, temperature rise still emerged as a likely major cause of increasing armed conflict. "We were very surprised to find that when you put things like economic growth and better governance into the mix, the temperature effect remains strong," said Dr Burke. At next month's UN climate summit in Copenhagen, governments are due to debate how much money to put into helping African countries prepare for and adapt to impacts of climate change. "Our findings provide strong impetus to ramp up investments in African adaptation to climate change by such steps as developing crop varieties less sensitive to extreme heat and promoting insurance plans to help protect farmers from adverse effects of the hotter climate," said Dr Burke. Nana Poku, Professor of African Studies at the UK's Bradford University, suggested that it also pointed up the need to improve mechanisms for avoiding and resolving conflict in the continent. "I think it strengthens the argument for ensuring we compensate the developing world for climate change, especially Africa, and to begin looking at how we link environmental issues to governance," he said. "If the argument is that the trend towards rising temperatures will increase conflict, then yes we need to do something around climate change, but more fundamentally we need to resolve the conflicts in the first place." Link: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/8375949.stm Richard.Black-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk | ||||

BBC World News TV "Hot Cities" -- Lagos, Nigeria, and Dakar, Senegal (episodes 1 and 5, respectively)

Hot Cities

Nov.15, 2009

BBC World News TV is now showing "Hot Cities," a new series about the effects of global warming around the world. If you can’t catch the segments on television, you can watch them on your computer. Each runs about 45 minutes.

Bursting at the Seams… Episode 1, Lagos Nigeria, 24 October 2009, by Producer/Director Joe Loncraine

“Hot Cities” begins in Lagos, one of the toughest and the fastest growing mega cities in the world — and a place very vulnerable to the threat of climate change. Large areas of the Lagos could be swamped by sea level rises. The city, one of the worlds fastest is a magnet for migrants across the whole of West Africa hoping to find a better life.

During preproduction of this film it soon emerged that our crew would need to be split across the three locations in the film. Since I was flying to Lagos, for the Nigeria section of the film, I would not be travelling to the two other locations, Alaska and the Maldives. Two countries considered some of the most beautiful places on earth and Lagos often branded as one of the world’s worst cities — I have to confess to a little disappointment. But, how wrong I was. Whilst Lagos is tough, dirty and over crowded, a little like my home city of London, it really feels like an exciting place to be and is a great place to film. A man on the street described it as the African New York and that is exactly what it feels like. Lagos is going through some major improvements in preparation to become the third largest city in the world. If developed in the right way, it could be an example to the rest of Africa’s rapidly growing cities. The excellent footage returned by the other crews from Alaska and the Maldives also differed from my expectations. In the Maldives I expected to see families living on the shores of idyllic beaches when in fact a huge proportion of the country live on a city island more densely populated than Manhattan. In Alaska there was little of the snow covered mountain ranges I expected, rather a massive expansive of flat muddy tundra. Overall the biggest surprise of making the film was learning how these three vastly different locations all face such a similar and present threat from their changing climates.

Water, water everywhere… Episode 2, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 31 October 2009, by producer/Director Cassie Farrell

Bangladesh is one of the countries most seriously affected by climate change. It is constantly battered by cyclones, coastal surges, overflowing rivers and violent downpours. Climate refugees from across the country are pouring into the capital, Dhaka. But Bangladesh is fighting back. In rural areas communities are developing new and ingenious ways of coping with climate change to help people survive, easing the pressure on the country’s capital.

Torrential rains, bursting rivers, cyclones, coastal surges - Bangladesh is at the sharp end of climate change.

People from rural areas pour into the capital Dhaka escaping flooding that has destroyed not only their homes but their livelihoods too. A population of 14 million is expected to increase to 50 million … miles of slums are home to these refugees who live quite literally piled on top of each-other.Whilst we’ve all seen pictures of Bangladeshis knee deep in water none of the film crew were prepared for the scenes of families living for weeks in stinking water, and mothers unable to find clean water for their children. This city is submerged - the slums are scenes from ‘Inferno’.

And yet, despite everything, people seem to have clung onto their spirit. Kushta, a mother of 4 works a ten hour shift laying bricks. She has a good idea of what global warming has done for her ‘my home is flooded, my husband cannot work on his land.’ She waves her fists in the air demanding the government find help for families like hers’. An old man driven from his home by floods is clear about where the fault lies ‘the rich nations have taken too much for too long, if they continue to ignore our rights we will take to the streets and fight for what is ours’

There are hundreds of voices like theirs’. They are loud and clear. We left feeling quite certain that the time has come for governments around the world to listen and to act.

The impact of climate change on the spread of disease and the affect on world health could be dramatic. In this episode of “Hot Cities” we go to Jakarta, a sprawling city of 12 million people. It’s also under threat from a new increase in dengue fever, for which there is no cure. Even rich countries are vulnerable. A deadly heat wave hit Chicago in 1995 killing hundreds of people. “Hot Cities” looks at the adaptation strategy Chicago has introduced to make sure it does not happen again.

The team of young men dressed in military style overalls and facemasks loaded their weapons and stood ready for action. This was Jakarta’s answer to climate change and we were there to follow them. Known simply as ‘foggers” these men use their “guns” to fire giant clouds of insecticide smothering entire neighbourhoods. The bewildered homeowners simply stand by and watch helplessly, inhaling the pungent fumes. This is Jakarta’s response to the extremely worrying increase in the painful and sometimes deadly mosquito borne disease, Dengue Fever. Everyone in this Asian city seems to have his or her own Dengue story; it’s so ubiquitous these days. Even our invaluable “fixer”, Dewa, was summoned back to his day job because so many of his colleagues were in hospital with the disease. It’s a looming crisis for the city. And everyone in Jakarta seems to agree on what’s to blame: climate change. The city’s scientists and the public alike all say it’s raining more and raining when it used to be dry. They say Jakarta’s traditional dry season has vanished allowing Dengue-carrying mosquitoes to flourish all year round. The authorities hope that “fogging” and other measure they are introducing will keep the disease under control. But it’s a big wish.

I lost track of how long we trudged through the snowstorm. All I could keep count of were my footsteps, as a way of pushing myself on. Every time I reached 100 I allowed myself to look up, exposing my face to the freezing wind to see if there was any sign of our destination. But, for what seemed like hours on end, there wasn’t. All I could see was a never-ending expanse of swirling white.

We were 5400 metres above sea level, on a glacier in the Peruvian Andes, heading towards a research camp where Lonnie Thompson, the world’s preeminent glaciologist, and his team were drilling into the ice core. Lonnie’s discovered that glaciers are melting at a rate which was previously inconceivable. As they disappear they will take most of the world’s fresh water supply with them.

Hard to imagine an ice-free world when you are traversing a glacier. Sometimes the only thing that kept my legs moving was the rope attaching me to the mountain guide, Americo. He walked ahead, prodding the snow with an axe. Often it would give way to reveal a deep crevasse. The more regular appearance of new ones is an ominous sign of global warming.

I felt so insignificant and small up on that massive glacier. But now, it too is helpless in the face of climate change. Up on it, there were times when I felt as if we were literally on top of the world. But with every crevasse that Americo uncovered I was reminded of how fragile things are and how quickly we could fall to the bottom.

Water security is going to be one of the most pressing issues as the world faces the challenge of climate change. If average global temperatures rise by only a few degrees most of the world’s glaciers will all but disappear, leading to floods and severe water shortages for millions of people. “Hot Cities” goes to Lima in Peru, one of the driest cities in the world, which relies heavily on the water from three rivers fed by glacial melt.

Half the world’s population face severe food shortages by the end of the century as climate change takes its toll on the global harvest. Drought in the Sahal, which runs through Senegal, means many climate migrants are flocking to the capital, Dakar, to find work to feed their families. “Hot Cities” follows migrants from their villages, where farming has almost been wiped out, to the city. This film also looks at what is being done to feed Senegal in the future.

Dusty, barren, desert. These are the words that entered my head as we trundled towards our location - the village of Diagle in Senegal. Our main interviewee Keba had taken us back home to where he used to farm before the droughts. He was one of many Climate Change refugees who have fled to the overstretched capital city of Dakar to feed his children. Once he met his family and spent time in his village we really saw him smile for the first time in our presence - it was like the huge weight of city-living had been lifted off of his shoulders. Next we found his fellow villager Ousmane who was due to leave for the capital next day. We felt privileged to witness Ousmane’s last remaining moments with his three year old son Ada before he left. Ironically in the developed world too - New South Wales, Australia - we met people who complained about younger farming generations leaving to find work in the city. What struck me making this film was the human cost of climate change - not only the obvious risk of starvation but how families and communities are being torn apart daily by this global phenomenon.

http://www.rockhopper.tv/hotcities/bursting_at_the_seams.html

http://www.rockhopper.tv/hotcities/water_water_everywhere.html

http://www.rockhopper.tv/hotcities/climate_bites.html

http://www.rockhopper.tv/hotcities/meltdown.html

http://www.rockhopper.tv/hotcities/feed_the_world.html

http://www.rockhopper.tv/hotcities/water_water_everywhere.html

http://www.rockhopper.tv/hotcities/climate_bites.html

http://www.rockhopper.tv/hotcities/meltdown.html

http://www.rockhopper.tv/hotcities/feed_the_world.html

Sunday, November 22, 2009

Tropical ice fields of the Mountains of the Moon (Rwenzori Mountains of the Congo and Uganda) set to disappear within 20 years

Fabled equatorial African icecaps to disappear

ScienceDaily, May 15, 2006 — Fabled equatorial icecaps will disappear within two decades, because of global warming, a study British and Ugandan scientists has found. In a paper to be published 17 May 2006 in Geophysical Research Letters, they report results from the first survey in a decade of glaciers in the Rwenzori Mountains of East Africa. An increase in air temperature over the last four decades has contributed to a substantial reduction in glacial cover, they say.

The Rwenzori Mountains--also known as the Mountains of the Moon--straddle the border between the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Republic of Uganda. They are home to one of four remaining tropical ice fields outside of the Andes and are renowned for their spectacular and rare flora and fauna. The mountains' legendary status was set during the second century, when the Greek geographer Ptolemy made a seemingly preposterous but ultimately accurate statement about snow-capped mountains at the equator in Africa: "The Mountains of the Moon whose snows feed the lakes, sources of the Nile."

The glaciers were first surveyed a century ago when glacial cover over the entire range was estimated to be 6.5 km² [2.5 square miles]. Recent field surveys and satellite mapping of glaciers conducted by researchers from University College London, Uganda's Makerere University, and the Ugandan Water Resources Management Department show that some glaciers are receding tens of metres [yards] each year and that the area covered by glaciers halved between 1987 and 2003. With less than 1 km² [half a square mile] of glacier ice remaining, the researchers expect these glaciers to disappear within the next twenty years.

Richard Taylor of the University College London Department of Geography, who led the study, says: "Recession of these tropical glaciers sends an unambiguous message of a changing climate in this region of the tropics. Considerable scientific debate exists, however, as to whether changes in temperature or precipitation are responsible for the shrinking of glaciers in the East African Highlands that also include Kilimanjaro [in Tanzania] and Mount Kenya." Taylor and his colleagues found that in the Rwenzori Mountains since the 1960s, there are clear trends toward increased air temperature without significant changes in precipitation.

A key focus of the research is the impact of climate change on water resources in Africa. Glacial recession in Rwenzori Mountains is not expected to affect alpine river flow, the scientists say, due to the small size of the remaining glaciers. It remains unclear, however, how the projected loss of the glaciers will affect tourism and local traditional belief systems that are based upon the snow and ice, known locally as "Nzururu."

"Considering the continent's negligible contribution to global greenhouse-gas emissions, it is a terrible irony that Africa, according to current predictions, will be most affected by climate change," added Taylor.

"Furthermore, the rise in air temperature is consistent with other regional studies that show how dramatic increases in malaria in the East African Highlands may arise, in part, from warmer temperatures, as mosquitoes are able to colonize previously inhospitable highland areas."

The research was funded by The Royal Geographical Society and The Royal Society.

Link: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2006/05/060515143818.htm

Saturday, November 21, 2009

Model predicts future deforestation in Central Africa

Nature, published online 20 November 2009; doi: 10.1038/news.2009.1100

Projections could help Central African nations in Copenhagen climate talks

by Anjali Naya, Nature News, November 20, 2009

A computer model that predicts future changes in the world's forests could strengthen the case of Central African nations that are calling for compensation in exchange for protecting their natural resources.

Forest management is expected to be a key point of discussion at the United Nations climate summit in Copenhagen in December. Countries will negotiate on how to reward rainforest nations for protecting their forests, a mechanism dubbed REDD for 'reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation'.

Deforestation rates in the Congo Basin rainforest — the second-largest rainforest on Earth — have hovered at around 0.15% per year for the past 15 years. But preliminary results from the model, unveiled this week, predict that forest cutting in the region will increase to 0.3–0.5% per year by 2020–2030.

Major rainforest countries that have historically had high deforestation rates — such as Indonesia (2.0%) and Brazil (0.6%) — are pushing for compensation that is based on historical trends. With a relatively high business-as-usual scenario, they are expected to reap above-average rewards for any decreases in deforestation.

But using historical trends will short-change the countries of the Congo Basin, some argue. Although in the past this region has had low deforestation rates, recent improvements in the road network as well as planned mining and timber projects are likely to increase deforestation rates considerably in coming years. "There are strong indications that Central African forests are at a critical turning point for the future," says Carlos de Wasseige, the coordinator of an EU-funded project called Forests of Central Africa, whuch hopes to set up a regional forest monitoring centre.

"Most proposals for [REDD] suggest that history is the best predictor of tomorrow," says Michael Obersteiner, who is leading the development of the forestry model at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, based in Laxenburg, Austria. "But for [Central African] countries, the forward-looking projections will be more reliable."

Obersteiner recognizes, however, that the model is only as good as the data going into it — and those data can often be difficult to obtain, either through lack of resources to collect them or because the information is held by private companies.

"The idea of publicly available reliable statistics escapes our country," says André Kondjo-Shoko, head of forest inventory at the Democratic Republic of the Congo's environment ministry. "The statistics don't represent reality."

Another problem is that the model does not account for a major driver of deforestation: illegal tree cutting for charcoal and timber.

The conservation group WWF now hopes to fill this data gap using a "geo-wiki," also unveiled this week, which provides a repository for forestry information. Modelled on the open-source principles of the online encyclopaedia Wikipedia, "it combines the principals of social networking with the craft of spatial mapping," says Leo Bottrill, who heads the geo-wiki project at the WWF's office in Washington, DC.

Bottrill started the geo-wiki after struggling to collate information about the Congo Basin region. For the past two years, he has been collecting baseline information on mineral deposits, forest concessions and planned infrastructure such as roads, railways and transmission lines. He hopes that the site's users will be able to contribute data and maps, either through the Internet or by text message, as well as commenting on and editing the content.

The WWF will launch a pilot of its geo-wiki for the Democratic Republic of the Congo in March 2010, and hopes the system will be fully functional by mid-2010. "We hope people will run with the idea," says Bottrill.

Link: http://www.nature.com/news/2009/091120/full/news.2009.1100.html

Model predicts future deforestation

Projections could help Central African nations in Copenhagen climate talks

by Anjali Naya, Nature News, November 20, 2009

A computer model that predicts future changes in the world's forests could strengthen the case of Central African nations that are calling for compensation in exchange for protecting their natural resources.

Forest management is expected to be a key point of discussion at the United Nations climate summit in Copenhagen in December. Countries will negotiate on how to reward rainforest nations for protecting their forests, a mechanism dubbed REDD for 'reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation'.

Deforestation rates in the Congo Basin rainforest — the second-largest rainforest on Earth — have hovered at around 0.15% per year for the past 15 years. But preliminary results from the model, unveiled this week, predict that forest cutting in the region will increase to 0.3–0.5% per year by 2020–2030.

Major rainforest countries that have historically had high deforestation rates — such as Indonesia (2.0%) and Brazil (0.6%) — are pushing for compensation that is based on historical trends. With a relatively high business-as-usual scenario, they are expected to reap above-average rewards for any decreases in deforestation.

But using historical trends will short-change the countries of the Congo Basin, some argue. Although in the past this region has had low deforestation rates, recent improvements in the road network as well as planned mining and timber projects are likely to increase deforestation rates considerably in coming years. "There are strong indications that Central African forests are at a critical turning point for the future," says Carlos de Wasseige, the coordinator of an EU-funded project called Forests of Central Africa, whuch hopes to set up a regional forest monitoring centre.

"Most proposals for [REDD] suggest that history is the best predictor of tomorrow," says Michael Obersteiner, who is leading the development of the forestry model at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, based in Laxenburg, Austria. "But for [Central African] countries, the forward-looking projections will be more reliable."

Model forest

The model, which has a resolution of 10–50 km2, is a combination of three global land-use models called GLOBIOM, G4M and EPIC. Its predictions are based on key global drivers of deforestation, including population growth and gross-domestic-product growth, as well as global demand and production of biofuel, timber and agricultural crops. The model works by calculating the profitability of forest clearance in certain areas on the basis of topography, soil composition and climate.Obersteiner recognizes, however, that the model is only as good as the data going into it — and those data can often be difficult to obtain, either through lack of resources to collect them or because the information is held by private companies.

"The idea of publicly available reliable statistics escapes our country," says André Kondjo-Shoko, head of forest inventory at the Democratic Republic of the Congo's environment ministry. "The statistics don't represent reality."

Another problem is that the model does not account for a major driver of deforestation: illegal tree cutting for charcoal and timber.

The conservation group WWF now hopes to fill this data gap using a "geo-wiki," also unveiled this week, which provides a repository for forestry information. Modelled on the open-source principles of the online encyclopaedia Wikipedia, "it combines the principals of social networking with the craft of spatial mapping," says Leo Bottrill, who heads the geo-wiki project at the WWF's office in Washington, DC.

Bottrill started the geo-wiki after struggling to collate information about the Congo Basin region. For the past two years, he has been collecting baseline information on mineral deposits, forest concessions and planned infrastructure such as roads, railways and transmission lines. He hopes that the site's users will be able to contribute data and maps, either through the Internet or by text message, as well as commenting on and editing the content.

The WWF will launch a pilot of its geo-wiki for the Democratic Republic of the Congo in March 2010, and hopes the system will be fully functional by mid-2010. "We hope people will run with the idea," says Bottrill.

Link: http://www.nature.com/news/2009/091120/full/news.2009.1100.html

Friday, November 20, 2009

Sean Cutler: Plant stress hormone (abscisic acid) inhibits growth during water scarcity

How crops survive drought

ScienceDaily, November 20, 2009 — Breakthrough research done earlier this year by a plant cell biologist at the University of California, Riverside, has greatly accelerated scientists' knowledge on how plants and crops can survive difficult environmental conditions such as drought.

Working on abscisic acid (ABA), a stress hormone produced naturally by plants, Sean Cutler's laboratory showed in April 2009 how ABA helps plants survive by inhibiting their growth in times when water is unavailable -- research that has important agricultural implications.

The Cutler lab, with contributions from a team of international leaders in the field, showed that in drought conditions certain receptor proteins in plants perceive ABA, causing them to inhibit an enzyme called a phosphatase. The receptor protein is at the top of a signaling pathway in plants, functioning like a boss relaying orders to the team below that then executes particular decisions in the cell.

Now recent published studies show how those orders are relayed at the molecular level. ABA first binds to the receptor proteins. Like a series of standing dominoes that begins to knock over, this then alters signaling enzymes that, in turn, activate other proteins resulting, eventually, in the halting of plant growth and activation of other protective mechanisms.

"I believe Sean's discovery is the most significant finding in plant biology this year and will have profound effects on agriculture worldwide," said Natasha Raikhel, the director of UC Riverside's Center for Plant Cell Biology, of which Cutler is a member. "Because the ABA receptor is so fundamentally important for understanding how plants perceive various environmental stresses, I am sure the strings of research that Sean's discovery sparks will be endless."

In only months since Cutler's discovery, six research papers in journals such as Science and Nature have been published that build on his work, a testament to the interest among plant scientists to nail down how exactly the stress signaling pathway works in plants. This intense activity in the field was expedited by Cutler's willingness to share information with colleagues before his own research was published -- an open approach that is at odds with the often cutthroat competition in hot scientific areas.

"This intense interest by the scientific community will certainly accelerate the development of new agrichemicals that can be used to control stress responses in crops, and I believe we need to work openly to tackle problems of such great importance," said Cutler, an assistant professor of plant cell biology in the Department of Botany and Plant Sciences. "There is also tremendous interest from industry, and we are moving closer to designing both improved chemicals that can control drought tolerance in crops and improved receptor proteins that can be used to enhance yield under drought conditions. Ultimately, my vision is to combine protein and chemical design to usher in a fundamentally new approach to crop protection. These recent papers are an important step towards realizing that goal."

Determining how the chemical switch works

One of the six research papers that builds on Cutler's work is published online Nov. 18 in Nature. The research, led by Jian-Kang Zhu, a professor of plant cell biology at UCR, fleshes out the domino pathway from the receptor down to the proteins that control plant growth.

"Freshwater is a precious commodity in agriculture," Zhu said. "Drought stress occurs when there is not enough freshwater. We wanted to understand how plants cope with drought stress at the molecular level. Such an understanding is necessary if we want to improve the drought tolerance of crop plants through either genetic engineering or marker-assisted breeding."

In their Nature paper, Zhu and his colleagues report on how they reconstituted in a test tube the process of information transfer from receptor to phosphatase, and all the way downstream to the protein that turns the gene on or off, and then ultimately to the gene itself.

"The ABA signaling pathway we reconstituted is arguably the most important pathway for plants to cope with drought stress." Zhu said. "This is the first time the whole pathway has been reconstituted in vitro. What is emerging is a clear picture of how the chemical switch works -- useful knowledge for designing improved chemical agents for application in crop fields."

Zhu explained that in vivo studies (done in the living body of the plant) involve thousands of proteins, which can complicate data interpretation. By doing the study in vitro (outside the living body of the plant) his lab avoids this problem, making it possible to determine the minimal number of components necessary and sufficient for the ABA response pathway.

Next in its research, the Zhu lab will use the knowledge of the ABA response pathway to make transgenic plants that will have substantially higher levels of drought tolerance, achieved by manipulating the levels and activities of the key components of the pathway. The lab also plans to investigate how drought stress triggers the production of ABA.

Zhu was joined in the research by Cutler and UCR's Hiroaki Fujii, Viswanathan Chinnusamy, and Sang-Youl Park. Americo Rodrigues, Silvia Rubio, Regina Antoni and Pedro L. Rodriguez of the Instituto de Biología Molecular y Celular de Plantas, Spain; and Jen Sheen of the Massachusetts General Hospital also collaborated on the study.

Zhu was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Currently, he has an appointment also at the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, Saudi Arabia.

The other five research papers that Cutler's research inspired discuss the molecular structure of the ABA receptor, showing in atomic detail how ABA functions to trigger signaling.

Link: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/11/091118143255.htm

Dust storms formed in Sahara linked to hurricane activity in Atlantic

Dust storms formed in Sahara linked to hurricane activity in Atlantic

Scientists are trying to understand what's causing the increasing number of more powerful hurricanes from the Atlantic Ocean in the last years. Some see it as part of a natural cycle in which hurricanes get worse for a decade or two before dwindling again.

Recent studies have pointed a potential relationship between warming sea surface temperatures caused by global warming and increases in the strength and number of hurricanes. Recently, a surprising link between a reduced hurricane activity in the Atlantic and thick clouds of dust that periodically rise from the Sahara Desert and blow off Africa's western coast has been noticed. Hurricanes are triggered by heat and moisture, and it seems that dry dust storms repress them before they fully develop.

Three hypothesis were formulated about how sand storms could affect hurricanes: dry air of sand storms could block the rising streams of air needed to increase the hurricane's power; midlevel winds accompanying the Saharan air cause wind cut, preventing rising currents from growing into storms or warmth absorbed by the dust in the air can stabilize the air currents' conditions, blocking rising air.

However, the dust storms could change a hurricane's direction further to the west increasing the possibility that it would reach the United States and Caribbean Islands. "This correlation between dust storms and hurricane activity are especially strong for the past few years," said study leader Amato Evan of the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

"In 2004, we saw an increase in dust activity and a decrease in hurricanes. In 2005, it was the exact opposite," Evan said.

"2005 was the busiest hurricane season on record. It included 26 named storms and 13 hurricanes, including Katrina, hailed as the most destructive U.S. storm ever. Preliminary analyses of this year's dust activity also support the theory," he continued.

The 2006 hurricane season has been weaker than forecasted, and this correlated with a high dust storm earlier in the year. "At the beginning of the year, we saw a lot of dust storms-just really continuous. Then, probably a few weeks ago, when we started seeing some of those hurricanes that were forming up in the Atlantic, we saw a real lack of dust activity," he told.

The dust storms form at the contact between hot, dryer desert air from the Sahara with cooler air from the Sahel (the region at the South of Sahara) to form winds that lift sand and dust into the atmosphere, where they are caught by strong trade winds and blown westward, across the Atlantic Ocean.

Some years, millions of tons of dust clouds that can cross the oceans in as little as five days, being detected in Caribbean and Florida, while in others there are almost no dust storms.

The researchers used satellite images to study the amount of African dust blown out over the Atlantic for the years 1982-2005 and compared that with tropical storm activity. They found an inverse relationship between tropical storms and dust. "While we cannot conclusively demonstrate a direct causal relationship, there appears to be a robust link between tropical cyclone activity and dust transport," they concluded.

"During periods of intense hurricane activity dust was relatively scarce in the atmosphere. In years when stronger dust storms rose up, on the other hand, fewer hurricanes swept through the Atlantic."

"While a great deal of work has focused on the links between [hurricanes] and warming ocean temperatures, this research adds another piece to the puzzle."

"People didn't understand the potential impact of dust until satellites allowed us to see how incredibly expansive these dust storms can be," Evan said in a statement.

"Sometimes during the summer, sunsets in Puerto Rico are beautiful, because of all the dust in the sky - well that dust comes all the way from Africa."

Co-author Jonathan Foley, also of the University of Wisconsin, added: "These findings are important because they show that long-term changes in hurricanes may be related to many different factors."

"What we don't know is whether the dust affects the hurricanes directly, or whether both [dust and hurricanes] are responding to the same large scale atmospheric changes around the tropical Atlantic," says Foley.

"That's what future research needs to find out."

Link: http://news.softpedia.com/news/Dust-Storms-Formed-in-Sahara-Linked-to-Hurricane-Activity-in-Atlantic-37736.shtml

Scientists are trying to understand what's causing the increasing number of more powerful hurricanes from the Atlantic Ocean in the last years. Some see it as part of a natural cycle in which hurricanes get worse for a decade or two before dwindling again.

Recent studies have pointed a potential relationship between warming sea surface temperatures caused by global warming and increases in the strength and number of hurricanes. Recently, a surprising link between a reduced hurricane activity in the Atlantic and thick clouds of dust that periodically rise from the Sahara Desert and blow off Africa's western coast has been noticed. Hurricanes are triggered by heat and moisture, and it seems that dry dust storms repress them before they fully develop.

Three hypothesis were formulated about how sand storms could affect hurricanes: dry air of sand storms could block the rising streams of air needed to increase the hurricane's power; midlevel winds accompanying the Saharan air cause wind cut, preventing rising currents from growing into storms or warmth absorbed by the dust in the air can stabilize the air currents' conditions, blocking rising air.

However, the dust storms could change a hurricane's direction further to the west increasing the possibility that it would reach the United States and Caribbean Islands. "This correlation between dust storms and hurricane activity are especially strong for the past few years," said study leader Amato Evan of the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

"In 2004, we saw an increase in dust activity and a decrease in hurricanes. In 2005, it was the exact opposite," Evan said.

"2005 was the busiest hurricane season on record. It included 26 named storms and 13 hurricanes, including Katrina, hailed as the most destructive U.S. storm ever. Preliminary analyses of this year's dust activity also support the theory," he continued.

The 2006 hurricane season has been weaker than forecasted, and this correlated with a high dust storm earlier in the year. "At the beginning of the year, we saw a lot of dust storms-just really continuous. Then, probably a few weeks ago, when we started seeing some of those hurricanes that were forming up in the Atlantic, we saw a real lack of dust activity," he told.

The dust storms form at the contact between hot, dryer desert air from the Sahara with cooler air from the Sahel (the region at the South of Sahara) to form winds that lift sand and dust into the atmosphere, where they are caught by strong trade winds and blown westward, across the Atlantic Ocean.

Some years, millions of tons of dust clouds that can cross the oceans in as little as five days, being detected in Caribbean and Florida, while in others there are almost no dust storms.

The researchers used satellite images to study the amount of African dust blown out over the Atlantic for the years 1982-2005 and compared that with tropical storm activity. They found an inverse relationship between tropical storms and dust. "While we cannot conclusively demonstrate a direct causal relationship, there appears to be a robust link between tropical cyclone activity and dust transport," they concluded.

"During periods of intense hurricane activity dust was relatively scarce in the atmosphere. In years when stronger dust storms rose up, on the other hand, fewer hurricanes swept through the Atlantic."

"While a great deal of work has focused on the links between [hurricanes] and warming ocean temperatures, this research adds another piece to the puzzle."

"People didn't understand the potential impact of dust until satellites allowed us to see how incredibly expansive these dust storms can be," Evan said in a statement.

"Sometimes during the summer, sunsets in Puerto Rico are beautiful, because of all the dust in the sky - well that dust comes all the way from Africa."

Co-author Jonathan Foley, also of the University of Wisconsin, added: "These findings are important because they show that long-term changes in hurricanes may be related to many different factors."

"What we don't know is whether the dust affects the hurricanes directly, or whether both [dust and hurricanes] are responding to the same large scale atmospheric changes around the tropical Atlantic," says Foley.

"That's what future research needs to find out."

Link: http://news.softpedia.com/news/Dust-Storms-Formed-in-Sahara-Linked-to-Hurricane-Activity-in-Atlantic-37736.shtml

Magnus Larsson: 6,000-km-long solidified sand wall proposed for the Sahara to stop desertification

Wall 'could stop desert spread'

by Jonathan Fildes, Technology reporter, BBC News, July 24, 2009

Desert sands, and the dunes that they form, are constantly on the move

A plan to build a 6,000-km-long wall across the Sahara Desert to stop the spread of the desert has been outlined.

The barrier -- formed by solidifying sand dunes -- would stretch from Mauritania in the west of Africa to Djibouti in the east.

The plan was put forward by architect Magnus Larsson at the TED Global conference in Oxford.

A 2007 UN study described desertification as "the greatest environmental challenge of our times."

"The threat is desertification. My response is a sandstone wall made from solidified sand," said Mr Larsson, who describes himself as a dune architect.

The sand would be stabilised by flooding it with bacteria that can set it like concrete in a matter of hours.

North African nations have promoted the idea of planting trees to form a Great Green Belt to prevent the spread of the sand.

A similar proposal -- known as the Green Wall of China -- has also been proposed to stop the spread of the Gobi Desert.

Ballooning idea

In 2007, the UN issued a report that said that one third of the Earth's population -- about two billion people -- are potential victims of desertification.

Magnus Larsson |

It is concerned that the slow creep of the sands will displace people and put new strains on natural resources and societies.

Problem areas include the former Soviet republics in central Asia, China and sub-Saharan Africa.

"It affects about 140 countries," Mr Larsson told BBC News.

Mr Larsson showed pictures of a village called Gidan-Kara in Nigeria which had had to be moved because of the creep of the dunes. He said it was one of many examples.

The architect's proposed wall across the desert would be a complement to, rather than a replacement, of the Great Green Belt proposal.

"It would provide physical support for the trees," he said.

Crucially, he said, it would leave a barrier even if the trees were removed.

"People are so poor in these countries and these regions that they chop them down for firewood."

The wall would effectively be made by "freezing" the shifting sand dunes, turning them into sandstone.

"The idea is to stop the desert using the desert itself," he said.

The sand grains would be bound together using a bacterium called Bacillus pasteurii commonly found in wetlands.

Moving dunes displace both people and crops |

"It is a microorganism which chemically produces calcite -- a kind of natural cement."

Mr Larsson got the idea for using the bacteria from a team at the University of California Davis, which had been investigating its use for solidifying the ground in earthquake prone areas.

Mr Larsson envisages injecting the dunes with the bacteria on a massive scale or using a barrage of giant bacteria-filled balloons.

"We allow the dune to wash over this structure then we would pop the balloon," he told BBC News.

The scheme would also have advantages for nearby populations, he said. For example, it could be excavated he said to provide shade, shelter or as a structure to collect water.

However, Mr Larsson admitted that the scheme faced numerous practical problems.

"There are many details left to explore in this story: political, practical, ethical, financial. My design is fraught with many challenges," he said.

"However, it's a beginning, it's a vision; if nothing else I would like this scheme to initiate a discussion," he added.

TED Global is a conference dedicated to "ideas worth spreading." It runs from the 21 to 24 July 2009 in Oxford, U.K.

Link to article: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/8166929.stm

A. T. Evan et al., Science 324, The role of aerosols in the evolution of tropical North Atlantic Ocean temperature anomalies

Science (8 May 2009), Vol. 324, No. 5928, pp. 778-781; DOI: 10.1126/science.1167404

Amato T. Evan* (Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies, and Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, U.S.A.), Daniel J. Vimont (Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, U.S.A.), Andrew K. Heidinger (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service; and Center for Satellite Applications and Research, 1225 West Dayton Street, Madison, WI 53706, U.S.A.), James P. Kossin (NOAA/NESDIS/National Climatic Data Center, Madison, WI 53706, U.S.A.) and Ralf Bennartz (Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, U.S.A.)

Abstract

Link to abstract: http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/324/5928/778

The role of aerosols in the evolution of tropical North Atlantic Ocean temperature anomalies

Amato T. Evan* (Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies, and Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, U.S.A.), Daniel J. Vimont (Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, U.S.A.), Andrew K. Heidinger (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service; and Center for Satellite Applications and Research, 1225 West Dayton Street, Madison, WI 53706, U.S.A.), James P. Kossin (NOAA/NESDIS/National Climatic Data Center, Madison, WI 53706, U.S.A.) and Ralf Bennartz (Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, U.S.A.)

Abstract

Observations and models show that northern tropical Atlantic surface temperatures are sensitive to regional changes in stratospheric volcanic and tropospheric mineral aerosols. However, it is unknown whether the temporal variability of these aerosols is a key factor in the evolution of ocean temperature anomalies. We used a simple physical model, incorporating 26 years of satellite data, to estimate the temperature response of the ocean mixed layer to changes in aerosol loadings. Our results suggest that the mixed layer’s response to regional variability in aerosols accounts for 69% of the recent upward trend, and 67% of the detrended and 5-year low pass–filtered variance, in northern tropical Atlantic Ocean temperatures.

*e-mail: atevan@wisc.edu

*e-mail: atevan@wisc.edu

Link to abstract: http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/324/5928/778

R. Bennartz: Airborne dust reduction plays larger than expected role in determining Atlantic temperature

Airborne dust reduction plays larger than expected role in determining Atlantic temperature

A dust storm off the coast of Morocco was imaged by NASA's MODIS Aqua meteorological satellite on March 12, 2009. A new study by UW-Madison researcher Amato Evan shows that variability of African dust storms and tropical volcanic eruptions can account for 70 percent of the warming North Atlantic Ocean temperatures observed during the past three decades. Since warmer water is a key ingredient in hurricane formation and intensity, dust and other airborne particles will play a critical role in developing a better understanding of these storms in a changing climate. (Credit: Photo: courtesy Amato Evan)

ScienceDaily, March 28, 2009 — The recent warming trend in the Atlantic Ocean is largely due to reductions in airborne dust and volcanic emissions during the past 30 years, according to a new study.

More than two-thirds of this upward trend in recent decades can be attributed to changes in African dust storm and tropical volcano activity during that time, report Evan and his colleagues at UW-Madison and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in a new paper. Their findings will appear in an upcoming issue of the journal Science and publish online March 26.

Evan and his colleagues have previously shown that African dust and other airborne particles can suppress hurricane activity by reducing how much sunlight reaches the ocean and keeping the sea surface cool. Dusty years predict mild hurricane seasons, while years with low dust activity — including 2004 and 2005 — have been linked to stronger and more frequent storms.

In the new study, they combined satellite data of dust and other particles with existing climate models to evaluate the effect on ocean temperature. They calculated how much of the Atlantic warming observed during the last 26 years can be accounted for by concurrent changes in African dust storms and tropical volcanic activity, primarily the eruptions of El Chichón in Mexico in 1982 and Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines in 1991.

In fact, it is a surprisingly large amount, Evan says. "A lot of this upward trend in the long-term pattern can be explained just by dust storms and volcanoes," he says. "About 70 percent of it is just being forced by the combination of dust and volcanoes, and about a quarter of it is just from the dust storms themselves."

The result suggests that only about 30 percent of the observed Atlantic temperature increases are due to other factors, such as a warming climate. While not discounting the importance of global warming, Evan says this adjustment brings the estimate of global warming impact on Atlantic more into line with the smaller degree of ocean warming seen elsewhere, such as the Pacific.

"This makes sense, because we don't really expect global warming to make the ocean [temperature] increase that fast," he says.

Volcanoes are naturally unpredictable and thus difficult to include in climate models, Evan says, but newer climate models will need to include dust storms as a factor to accurately predict how ocean temperatures will change.

"We don't really understand how dust is going to change in these climate projections, and changes in dust could have a really good effect or a really bad effect," he says.

Satellite research of dust-storm activity is relatively young, and no one yet understands what drives dust variability from year to year. However, the fundamental role of the temperature of the tropical North Atlantic in hurricane formation and intensity means that this element will be critical to developing a better understanding of how the climate and storm patterns may change.

"Volcanoes and dust storms are really important if you want to understand changes over long periods of time," Evan says. "If they have a huge effect on ocean temperature, they're likely going to have a huge effect on hurricane variability as well."

The new paper is coauthored by Ralf Bennartz and Daniel Vimont of UW-Madison and Andrew Heidinger and James Kossin of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and UW-Madison.

Link: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/03/090326141553.htm

Labels:

Atlantic hurricanes,

dust,

ocean temperatures

Less dust from Africa warms the tropical North Atlantic Ocean, creating conditions for more hurricanes

Less dusty air warms Atlantic, may spur hurricanes

by Alister Doyle, Environment Correspondent, Reuters, March 26, 2009OSLO (Reuters) -- A decline in sun-dimming airborne dust has caused a fast warming of the tropical North Atlantic in recent decades, according to a study that might help predict hurricanes on the other side of the ocean.

About 70% of the warming of the Atlantic since the early 1980s was caused by less dust, blown from Saharan sandstorms or caused by volcanic eruptions, U.S.-based scientists wrote in the journal Science.

Clouds of dust can be blown thousands of kilometers (miles) and reflect some of the sun's rays back into space.

"Since 1980 tropical North Atlantic Ocean temperatures have been rising at a rate of nearly 0.25 °C (0.45 °F) per decade," they wrote on Thursday.

In the past, the rapid temperature rise had been blamed on factors such as global warming or shifts in ocean currents. Warmer temperatures may spur more hurricanes, which need sea surface temperatures of about 28 °C (82.4 °F) to form.

A sea temperature difference of just one degree Fahrenheit separated 1994, a quiet hurricane year, from a record 2005 when storms included Hurricane Katrina, which devastated New Orleans, according to a University of Wisconsin-Madison statement.

"We were surprised" by the big role of dust on Atlantic temperatures, said Ralf Bennartz, a professor at the university and a co-author of the study written with experts at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

COOLER

In past decades "there was much more dust blowing from (Africa) onto the Atlantic and cooling the sea and ... potentially suppressing hurricane intensity," he told Reuters. No other ocean receives so much dust.

More droughts in Africa in the 1980s, for instance, meant more dust in the air, he said of the study of satellite data and climate models. Annual emissions of dust from North Africa have been estimated at between 240 million and 1.6 billion tonnes.

Bennartz said the scientists were trying to work out, for instance, if wet weather in North Africa could mean less dust and in turn point to fewer hurricanes battering the United States or Caribbean islands.

Big volcanic eruptions were El Chichon in Mexico in 1982 and Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines in 1991. Both dimmed the sun.

The study suggests that only 30% of the warming of the Atlantic can be explained by factors other than dust, for instance global warming blamed by the U.N. Climate Panel on emissions of greenhouse gases from burning fossil fuels.

"This makes sense, because we don't really expect global warming to make the ocean (temperatures) increase that fast," said Amato Evan, a researcher at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who was lead author.

Bennartz said it was unclear how climate change might affect overall dust amounts blown from Africa this century.

(Editing by Janet Lawrence)

Link to article: http://www.reuters.com/article/environmentNews/idUSTRE52P5T520090326

Labels:

Atlantic hurricanes,

dust,

ocean temperatures

I. S. Castañeda et al., PNAS 2009, Wet phases in the Sahara/Sahel region and human migration patterns in North Africa

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, published online before print November 12, 2009; doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905771106

Edited by Thure E. Cerling, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, and approved October 1, 2009 (received for review May 25, 2009)

Abstract

*Correspondence e-mail: isla.castaneda@nioz.nl

Link to abstract: http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2009/11/11/0905771106.abstract

Link to free, full, open-access article: http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2009/11/11/0905771106.full.pdf+html

Wet phases in the Sahara/Sahel region and human migration patterns in North Africa

Isla S. Castañedaa,1, Stefan Mulitzab, Enno Schefußb, Raquel A. Lopes dos Santosa, Jaap S. Sinninghe Damstéa and Stefan SchoutenaEdited by Thure E. Cerling, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, and approved October 1, 2009 (received for review May 25, 2009)

Abstract